MODERATOR (200 Words -Sent to New York Times)::

Agree with Mr. Ramadan that one should prime the knowledge with a different book before reading Qur’aan. I highly recommend Karen Armstrong’s book Muhammad, the book that changed my perspectives.

Agree with Mr. Ramadan that one should prime the knowledge with a different book before reading Qur’aan. I highly recommend Karen Armstrong’s book Muhammad, the book that changed my perspectives.

Glad to see the assertion, “The Koran belongs to everyone, free of distinction and of hierarchy.” Indeed, none of the holy books should belong to any one in particular, their message if for the whole humanity.

Approaches to studying Qur’aan vary. I believe if we can study from the point of view of a guidance book to humanity and in the light of co-existence, then we see a common sense develop, that is on par and reflective of the goodness emitted in Qur’aan.

The key is your orientation. There is beautiful verse in Qur’aan, Al-Inshiqaq, Surah 84:7-15: Each person will be given a book. Those who are given their books in their right hands (understanding the book correctly) will be judged leniently; and they will return to their people joyfully. But those who are given their books in their left hands (misunderstanding) will call their own destruction on themselves, and burn in the fire of hell. There are the people who have never cared for their neighbors; they thought they would never return to God. Their Lord watches all that people do.

There is a clear distinction between the word of God and its interpretation. Interpretation is human and is subject to one’s disposition, whereas the word of God is the final word. It is incredible how some of them are deliberately mistranslated by Crusaders and the defenders. Much of the jumping the Neocon jacks do is based on those cruel misrepresentations, which they have built their theories on those false foundations. Thank God there are over 20 translations on the market now.

Reading the Koran

By TARIQ RAMADAN

Published: January 6, 2008

For Muslims the Koran stands as the Text of reference, the source and the essence of the message transmitted to humanity by the creator. It is the last of a lengthy series of revelations addressed to humans down through history. It is the Word of God — but it is not God. The Koran makes known, reveals and guides: it is a light that responds to the quest for meaning. The Koran is remembrance of all previous messages, those of Noah and Abraham, of Moses and Jesus. Like them, it reminds and instructs our consciousness: life has meaning, facts are signs.

It is the Book of all Muslims the world over. But paradoxically, it is not the first book someone seeking to know Islam should read. (A life of the Prophet or any book presenting Islam would be a better introduction.) For it is both extremely simple and deeply complex. The nature of the spiritual, human, historical and social teachings to be drawn from it can be understood at different levels. The Text is one, but its readings are multiple.

For the woman or the man whose heart has made the message of Islam its own, the Koran speaks in a singular way. It is both the Voice and the Path. God speaks to one’s innermost being, to his consciousness, to his heart, and guides him onto the path that leads to knowledge of him, to the meeting with him: “This is the Book, about it there can be no doubt; it is a Path for those who are aware of God.” More than a mere text, it is a traveling companion to be chanted, to be sung or to be heard.

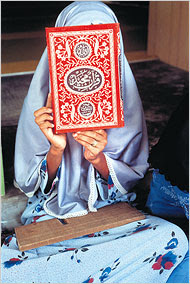

Throughout the Muslim world, in mosques, in homes and in the streets, one can hear magnificent voices reciting the divine Words. Here, there can be no distinction between religious scholars (ulema) and laymen. The Koran speaks to each in his language, accessibly, as if to match his intelligence, his heart, his questions, his joy as well as his pain. This is what the ulema have termed reading or listening as adoration. As Muslims read or hear the Text, they strive to suffuse themselves with the spiritual dimension of its message: beyond time, beyond history and the millions of beings who populate the earth, God is speaking to each of them, calling and reminding each of them, inviting, guiding, counseling and commanding. God responds, to her, to him, to the heart of each: with no intermediary, in the deepest intimacy.

No need for studies and diplomas, for masters and guides. Here, as we take our first steps, God beckons us with the simplicity of his closeness. The Koran belongs to everyone, free of distinction and of hierarchy. God responds to whoever comes to his Word. It is not rare to observe women and men, poor and rich, educated and illiterate, Eastern and Western, falling silent, staring into the distance, lost in thought, stepping back, weeping. The search for meaning has encountered the sacred, God is near: “Indeed, I am close at hand. I answer the call of him who calls me when s/he calls.”

A dialogue has begun. An intense, permanent, constantly renewed dialogue between a Book that speaks the infinite simplicity of the adoration of the One, and the heart that makes the intense effort necessary to liberate itself, to meet him. At the heart of every heart’s striving lies the Koran. It holds out peace and initiates into liberty.

Indeed, the Koran may be read at several levels, in quite distinct fields. But first, the reader must be aware of how the Text has been constructed. The Koran was revealed in sequences of varying length, sometimes as entire chapters (suras), over a span of 23 years. In its final form, the Text follows neither a chronological nor strictly thematic order. Two things initially strike the reader: the repetition of Prophetic stories, and the formulas and information that refer to specific historical situations that the Koran does not elucidate. Understanding, at this first level, calls for a twofold effort on the part of the reader: though repetition is, in a spiritual sense, a reminder and a revivification, in an intellectual sense it leads us to attempt to reconstruct. The stories of Eve and Adam, or of Moses, are repeated several times over with differing though noncontradictory elements: the task of human intelligence is to recompose the narrative structure, to bring together all the elements, allowing us to grasp the facts.

But we must also take into account the context to which these facts refer: all commentators, without distinction as to school of jurisprudence, agree that certain verses of the revealed Text (in particular, but not only, those that refer to war) speak of specific situations that had arisen at the moment of their revelation. Without taking historical contingency into account, it is impossible to obtain general information on this or that aspect of Islam. In such cases, our intelligence is invited to observe the facts, to study them in reference to a specific environment and to derive principles from them. It is a demanding task, which requires study, specialization and extreme caution. Or to put it differently, extreme intellectual modesty.

The second level is no less demanding. The Koranic text is, first and foremost, the promulgation of a message whose content has, above all, a moral dimension. On each page we behold the ethics, the underpinnings, the values and the hierarchy of Islam taking shape. In this light, a linear reading is likely to disorient the reader and to give rise to incoherence, even contradiction. It is appropriate, in our efforts to determine the moral message of Islam, to approach the Text from another angle. While the stories of the Prophets are drawn from repeated narrations, the study of ethical categories requires us, first, to approach the message in the broadest sense, then to derive the principles and values that make up the moral order. The methods to be applied at this second level are exactly the opposite of the first, but they complete it, making it possible for religious scholars to advance from the narration of a prophetic story to the codification of its spiritual and ethical teaching.

But there remains a third level, which demands full intellectual and spiritual immersion in the Text, and in the revealed message. Here, the task is to derive the Islamic prescriptions that govern matters of faith, of religious practice and of its fundamental precepts. In a broader sense, the task is to determine the laws and rules that will make it possible for all Muslims to have a frame of reference for the obligations, the prohibitions, the essential and secondary matters of religious practice, as well as those of the social sphere. A simple reading of the Koran does not suffice: not only is the study of Koranic science a necessity, but knowledge of segments of the prophetic tradition is essential. One cannot, on a simple reading of the Koran, learn how to pray. We must turn to authenticated prophetic tradition to determine the rules and the body movements of prayer.

As we can see, this third level requires singular knowledge and competence that can only be acquired by extensive, exhaustive study of the texts, their surrounding environment and, of course, intimate acquaintance with the classic and secular tradition of the Islamic sciences. It is not merely dangerous but fundamentally erroneous to generalize about what Muslims must and must not do based on a simple reading of the Koran. Some Muslims, taking a literalist or dogmatic approach, have become enmeshed in utterly false and unacceptable interpretations of the Koranic verses, which they possess neither the means, nor on occasion the intelligence, to place in the perspective of the overarching message. Some orientalists, sociologists and non-Muslim commentators follow their example by extracting from the Koran certain passages, which they then proceed to analyze in total disregard for the methodological tools employed by the ulema.

Above and beyond these distinct levels of reading, we must take into account the different interpretations put forward by the great Islamic classical tradition. It goes without saying that all Muslims consider the Koran to be the final divine revelation. But going back to the direct experience of the Companions of the Prophet, it has always been clear that the interpretation of its verses is plural in nature, and that there has always existed an accepted diversity of readings among Muslims.

Some have falsely claimed that because Muslims believe the Koran to be the word of God, interpretation and reform are impossible. This belief is then cited as the reason why a historical and critical approach cannot be applied to the revealed Text. The development of the sciences of the Koran — the methodological tools fashioned and wielded by the ulema and the history of Koranic commentary — prove such a conclusion baseless. Since the beginning, the three levels outlined above have led to a cautious approach to the texts, one that obligates whoever takes up the task to be in harmony with his era and to renew his comprehension. Dogmatic and often mummified, hidebound readings clearly reflect not upon the Author of the Text, but upon the intelligence and psychology of the person reading it. Just as we can read the work of a human author, from Marx to Keynes, in closed-minded and rigid fashion, we can approach divine revelation in a similar manner. Instead, we should be at once critical, open-minded and incisive. The history of Islamic civilization offers us ample proof of this.

When dealing with the Koran, it is neither appropriate nor helpful to draw lines of demarcation between approaches of the heart and of the mind. All the masters of Koranic studies without exception have emphasized the importance of the spiritual dimension as a necessary adjunct to the intellectual investigation of the meaning of the Koran. The heart possesses its own intelligence: “Have they not hearts with which to understand,” the Koran calls out to us, as if to point out that the light of intellect alone is not enough. The Muslim tradition, from the legal specialists to the Sufi mystics, has continuously oscillated between these two poles: the intelligence of the heart sheds the light by which the intelligence of the mind observes, perceives and derives meaning. As sacred word, the Text contains much that is apparent; it also contains the secrets and silences that nearness to the divine reveals to the humble, pious, contemplative intelligence. Reason opens the Book and reads it — but it does so in the company of the heart, of spirituality.

For the Muslim’s heart and conscience, the Koran is the mirror of the universe. What the first Western translators, influenced by the biblical vocabulary, rendered as “verse” means, literally, “sign” in Arabic. The revealed Book, the written Text, is made up of signs, in the same way that the universe, in the image of a text spread out before our eyes, abounds with these very signs. When the intelligence of the heart — and not analytical intelligence alone — reads the Koran and the world, the two speak to one another, echo one another; each one speaks of the other and of the Unique One. The signs remind us of meaning: of birth, of life, of feeling, of thought, of death.

But the echo is deeper still, and summons human intelligence to understand revelation, creation and their harmony. Just as the universe possesses its fundamental laws and its finely regulated order — which humans, wherever they may be, must respect when acting upon their environment — the Koran lays down laws, a moral code and a body of practice that Muslims must respect, whatever their era and their environment. These are the invariables of the universe, and of the Koran. Religious scholars use the term qat’i (“definitive,” “not subject to interpretation”) when they refer to the Koranic verses (or to the authenticated Prophetic tradition, ahadith) whose formulation is clear and explicit and offers no latitude for figurative interpretation. In like manner, creation itself rests upon universal laws that we cannot ignore. The consciousness of the believer likens the five pillars of Islam to the laws of gravitation: they constitute an earthly reality beyond space and time.

As the universe is in constant motion, rich in an infinite diversity of species, beings, civilizations, cultures and societies, so too is the Koran. In the latitude of interpretation offered by the majority of its verses, by the generality of the principles and actions that it promulgates with regard to social affairs, by the silences that run through it, the Koran allows human intelligence to grasp the evolution of history, the multiplicity of languages and cultures, and thus to insinuate itself into the windings of time and the landscapes of space.

Some have falsely claimed that because Muslims believe the Koran to be the word of God, interpretation and reform are impossible. This belief is then cited as the reason why a historical and critical approach cannot be applied to the revealed Text. The development of the sciences of the Koran — the methodological tools fashioned and wielded by the ulema and the history of Koranic commentary — prove such a conclusion baseless. Since the beginning, the three levels outlined above have led to a cautious approach to the texts, one that obligates whoever takes up the task to be in harmony with his era and to renew his comprehension. Dogmatic and often mummified, hidebound readings clearly reflect not upon the Author of the Text, but upon the intelligence and psychology of the person reading it. Just as we can read the work of a human author, from Marx to Keynes, in closed-minded and rigid fashion, we can approach divine revelation in a similar manner. Instead, we should be at once critical, open-minded and incisive. The history of Islamic civilization offers us ample proof of this.

When dealing with the Koran, it is neither appropriate nor helpful to draw lines of demarcation between approaches of the heart and of the mind. All the masters of Koranic studies without exception have emphasized the importance of the spiritual dimension as a necessary adjunct to the intellectual investigation of the meaning of the Koran. The heart possesses its own intelligence: “Have they not hearts with which to understand,” the Koran calls out to us, as if to point out that the light of intellect alone is not enough. The Muslim tradition, from the legal specialists to the Sufi mystics, has continuously oscillated between these two poles: the intelligence of the heart sheds the light by which the intelligence of the mind observes, perceives and derives meaning. As sacred word, the Text contains much that is apparent; it also contains the secrets and silences that nearness to the divine reveals to the humble, pious, contemplative intelligence. Reason opens the Book and reads it — but it does so in the company of the heart, of spirituality.

For the Muslim’s heart and conscience, the Koran is the mirror of the universe. What the first Western translators, influenced by the biblical vocabulary, rendered as “verse” means, literally, “sign” in Arabic. The revealed Book, the written Text, is made up of signs, in the same way that the universe, in the image of a text spread out before our eyes, abounds with these very signs. When the intelligence of the heart — and not analytical intelligence alone — reads the Koran and the world, the two speak to one another, echo one another; each one speaks of the other and of the Unique One. The signs remind us of meaning: of birth, of life, of feeling, of thought, of death.

But the echo is deeper still, and summons human intelligence to understand revelation, creation and their harmony. Just as the universe possesses its fundamental laws and its finely regulated order — which humans, wherever they may be, must respect when acting upon their environment — the Koran lays down laws, a moral code and a body of practice that Muslims must respect, whatever their era and their environment. These are the invariables of the universe, and of the Koran. Religious scholars use the term qat’i (“definitive,” “not subject to interpretation”) when they refer to the Koranic verses (or to the authenticated Prophetic tradition, ahadith) whose formulation is clear and explicit and offers no latitude for figurative interpretation. In like manner, creation itself rests upon universal laws that we cannot ignore. The consciousness of the believer likens the five pillars of Islam to the laws of gravitation: they constitute an earthly reality beyond space and time.

As the universe is in constant motion, rich in an infinite diversity of species, beings, civilizations, cultures and societies, so too is the Koran. In the latitude of interpretation offered by the majority of its verses, by the generality of the principles and actions that it promulgates with regard to social affairs, by the silences that run through it, the Koran allows human intelligence to grasp the evolution of history, the multiplicity of languages and cultures, and thus to insinuate itself into the windings of time and the landscapes of space.

Tariq Ramadan is a professor of Islamic studies at Oxford and at Erasmus University in the Netherlands.

FURTHER COMMENTS

Marylou – Reading Qur’aan

Marylou: Mike, First question — our understanding of this would be that God does NOT punish, but we reap the consequences of our own ignorance, therefore, we have no fear of God, but we do fear the consequences of our ignorance, thus we pray for enlightenment. Is Islam saying that in addition to reaping the consequences of our ignorance, there is additional punishment from God? Also, I assume that “burning in hell fire” is a metaphor?

Mike Ghouse: No, there is no additional punishment from God. No one needs to fear God. God has established great systems that run precisely on their own. What we need to fear is the consequences for our ignorance, which are set. However, God may see the good things we do, unawares of ourselves and may grace us with peace in his kingdom, that is purely discretionary, but if we have done good to others, treated others as we would wanted to be treated, then there is no fear of any kind. All are guaranteed a pass to an eternal blissful state of existence – which has come to be known as Heaven.

Marylou – Second question: “There is a clear distinction between the word of God and its interpretation. Interpretation is human and is subject to one’s disposition” We agree — that’s why Jesus said to “call no man our authority on earth; we have one authority who is in heaven.” As Christians, we are to question interpretations of the Bible we don’t understand or agree with another’s interpretation, and ask God for personal insight.

Mike Ghouse: Indeed, Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) had said in his last sermon, I am leaving this book (Qur’aan) to you to understand it on your own. He further said that no one is going to be appointed to interpret this book for you. If we are going to be accountable for our deeds, then the burden is on us to understand, not blame any one else. Individual responsibility is huge in Islamic teachings, it is further clarified that on the day of reckoning, no one will be there to give you a hand, you are on your own, and your parents are figuring it out for themselves as your kids are. I will sum with a verse from the Hindu scriptures – finding the truth is your own responsibility.

Marylou -Third Question: How do Muslims deal with interpretation? Do they rely solely on Imams? What if Imams differ? Who is the final authority as to what is the “word of God”?

Mike Ghouse: Like any discipline, business or an act of life, we look for guidance from the experienced ones; religion is no different. There is no final authority on what is God’s word, there is final responsibility though – that is the individual. Occasionally there is talk about the Caliph – it is really a pipe dream, as Islam does not give room for middlemen or women between God and us. No one’s interpretation is final. You are responsible for creating peace within and around you, if your actions fail; you are responsible, if you do well, you should be proud of it.

Caveat: The Shia denomination and its sub-denominations do give room for their Imam to interpret the religion for them and it works for them. Following the imam does bring the peace within and around oneself, as the entire group follows the same rule. In the Sunni tradition there is respect for the imam, but his word is not final.

In Sunni or Shia dominated nations, Sharia laws are instituted, theoretically they will work if every one were to follow the same rules. Sharia laws are not from God, but made by men for men …for the sake of keeping the sanity and a balance in a given society. The laws are extremely sensitive, some time it is hair splitting and sadly have led to abuse by the enforcers and hence Sharia gets a bad rap.

Most of the Sharia laws are ‘how to’ rules interpreted from Qur’aan and are appreciated. Mistakes have been made and there is no consensus on the logistics of following issues; Divorce, Apostasy, Conversions and Treatment of Women. Community at large needs to review this issue seriously. Missing which will tempt the newer generation to paint the whole Sharia laws with a negative label.

Shamim Siddiqi – Reading Qur’aan

My Dear Br Ghouse, ASA”Coexistence” is a very vague and extremely relative terminology. It means that necessarily all the constituents are at par, enjoying equal rights have no fear from anyone or nay side and all have equal opportunities to live together. If the situation is not such, it would be a farce, a misnomer, an illusion and a self deception. I wish you could first have strive hard to attain that “blessed” society and environment in this “half-fed-half naked” world that stands full of totally exploited communities/people in this country and around the continents of Asia, Europe,, Africa and S America.

You may be nurturing a wish but on false premises and erratic presumptionsLet us first try to deliver Justice to suffering humanity at all levels. Then please desire for your cherished “coexistence” and for that justice humanity has to be obedient to its Creator and Sustainer and feel always accountable to Him after death. Only with this message you will be able to deliver justice, establish peace and security on the abode of man. Only then they will be able to live in peace and coexist together, not before that.Hope you will please adjust your motto and be more realistic. We all are struggling for the same cause and therefore should not stand at pole asunder.With best regards.Shamim Siddiqi

Mike Ghouse– Brother Shamim your comments are appreciated. Co-existence is the goal we all need to drive towards, certainly with liberty and justice for all. Co-existence is learning to accept other people’s rights, and acknowledging the areas of conflict and working our best to let the conflicts not destroy each other.