I am a longtime believer in the power of writing by hand, but it took a museum exhibit in a converted mosque in Beersheba, Israel, to teach me that the bridge among Chinese culture, the Islamic world and Western civilization was made of paper. Two thousand years ago, paper was invented in China, and it reached the Muslim world through Chinese prisoners of war captured in 751 C.E. Paper-making knowledge then made its way to Iraq, Syria and North Africa, so the paper in my hands is evidence of the Muslim world’s move from the Middle East to North Africa to Europe.

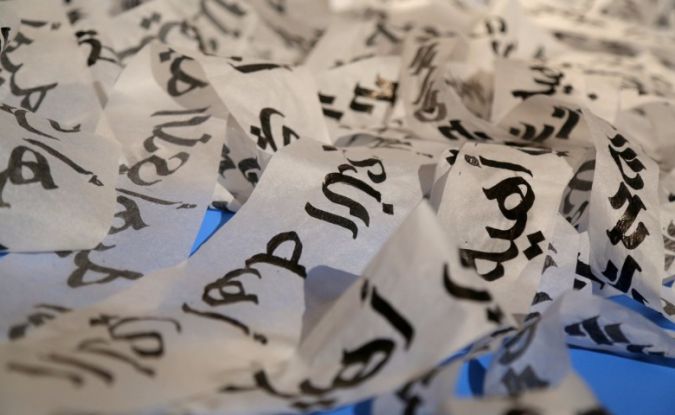

Thinking about paper is certainly a different way of thinking about history. “Maktub — Traditional and Contemporary Calligraphy Between East and West,” a remarkable though small exhibit in a magnificent mosque in Beersheba’s Old City that is now the Museum of Islamic and Near Eastern Cultures, focuses on how Muslim culture promoted a reverence for the act of writing, with scribes engaged in copying sacred texts, and often illustrating them elaborately. This is a welcome relief from what would be a more typical approach of emphasizing battles between Christianity and Islam for territory and power, with the Jewish community often caught in between, fighting for its life and breath,

I returned twice to “Maktub,” and twice looked down to admire the multicolored fountain at the entrance, designed by Arman Darian, an Armenian who moved to Jerusalem. Then I looked up toward the stunning arches of the mosque-turned-museum as the security guard watched intently; he had, I think, gotten used to the arches’ beauty.

The exhibit opens in a surprising way — with a large contemporary photograph of a woman’s feet, covered with Arabic writing. To the left of the feet I saw lettering that seemed both familiar and unfamiliar. Called Aravrit, it is an “experimental writing system” created by the artist Liron Lavi Turkenich, composed of Arabic on the upper half of each word and Hebrew on the bottom half; to my eye it looked a little medieval, like Rashi script. But there is a very contemporary ethos behind Aravrit, which even has its own Facebook page.

“In Aravrit, one can read any chosen language without ignoring the other one, which is always present,” the free postcards with individual words in Aravrit explain. But the trick to reading Aravrit, as I learned from too much time with the rather addictive postcards, is to let your eye focus on the language you do read. You can understand it with just Hebrew, or just Arabic, but you must have at least one.

For writing nerds, in any language, the exhibit feels like a love letter to the act of writing. I admired two 19th-century pen cases from Iran — one in papier-mâché and one in steel, inlaid with gold and silver — that looked like prized possessions of writers long gone. I looked longingly at a 12th-century brass inkwell from Iran, made of repoussé with silver, and at a 19th-century pencil sharpener from Turkey that, made of steel with gold thread, any editor might covet.

Then there is the writing itself, like the breathy, ethereal page of blessings written by a highly skilled calligrapher. Surrounded by a faded turquoise frame, and composed of ink, watercolor and gold on paper in 18th-century Iran, it looks like an appeal to the heavens. Next to it is a far different piece, made of ink and gold on paper a century later in Iran. The writing looks bold and definite, and it is many shades darker; it’s the opening chapter of the Quran. A few paces away is a micrographic Quran made of ink, watercolor and gold in Karachi, Pakistan, in 1845. To the naked eye, the text looks like a gray block, but with a magnifying glass, the tiny letters are revealed. Reading about the pre-paper versions of the Quran — on tree bark, bone and leather — is its own revelation: I thought of Torah scrolls made of animal skin.

Ibn Muqla (866-940) first established calligraphy as an art. Years of training were required to acquire the skill to transcribe holy texts, scientific writing and literature, as well as bureaucratic and legal documents. Looking at the Arabic letters, I thought of how the calligrapher resembles the sofer, who handwrites the Torah and other holy texts. These texts include the scrolls inside a mezuza, which appear on each doorpost in a Jewish home and is often kissed when one enters a room.

In the 14th century, the belief that Arabic letters had magical powers was widespread. Scholars and mystics searched for hidden meanings in letters; Sufism, the mystical branch of Islam, divides the 28 Arabic letters into four categories — earth, fire, air and water. I couldn’t help myself: I flashed back to gematria, the Jewish system where each Hebrew letter has a numerical value. Many commentators use gematria to come up with additional layers of meaning for problematic words or passages in the Bible.

The many amulets on display here, once worn around a neck or placed in a special spot in the home, attest to the Muslim belief in the power of letters; my favorite was a palm-sized amulet against snakes and scorpions from Morocco, circa 1900. I thought of the unforgettable story by Shmuel Yosef Agnon, Israel’s Nobel Prize winner in fiction, about a childless couple and a kamea *or amulet. As I looked at an 1851 “amulets manuscript” from Yemen that is part Hebrew and part Arabic, I thought of those characters’ belief in the *kameah’s power to bring them a child. The book, in red and black ink, mixes languages as it explains amulets and their powers in intricate detail.

The museum tries hard to encourage thinking of parallels between Islam and Judaism, like displaying an 1892 ketubah, or marriage contract, from Iran next to a very similar-looking government document. When I scrutinized the ketubah, the museum docent pointed out the tiny Hebrew signatures alongside the grand Arabic calligraphy. I looked closer, and noticed what looked like a fingerprint. I wondered aloud if it was the signature of an illiterate family member, or maybe it was a faded seal.

“Want to know something interesting? A group of Bedouin girls visited earlier today,” the docent told me. “They said that at the top of the ketubah there are verses from the Quran.”

That was indeed interesting. So was a striking 1998 painting by Farid Abu-Shakra titled “Flowerpot” that features red flowers and Arabic writing that reads — “Farewell to you, my four children” — over and over. It’s about a mother who lost her four sons in the second intifada, the wall text says; the color red “symbolizes love and pain.”

The date of the painting — 1998 — seemed a bit off to me. I found myself Googling the exact dates of the second intifada, the start of which is usually dated to Ariel Sharon’s visit to the Temple Mount in 2000, a time when I lived in and reported from Jerusalem. But when I asked for clarification, the museum docent said she thought the painting referred to the mehumot, or riots, that occurred in the late 1990s and are sometimes grouped with the second intifada.

Fair enough.

Walking through again, I found myself less moved by the parallels between Muslim and Jewish traditions and more moved by the idea that for centuries writing has been both decorative and meaningful, but, more deeply, both sacred and mercenary. Paper may be on its way out, but the contradiction inherent in writing may not change: It is still both holy work and paid work, sometimes controversial and sometimes mundane. It’s always trying to bridge the world of writer and reader; done right, it’s still trying to surpass the headlines, and hoping to outlast time.

Article Courtesy – forward.com